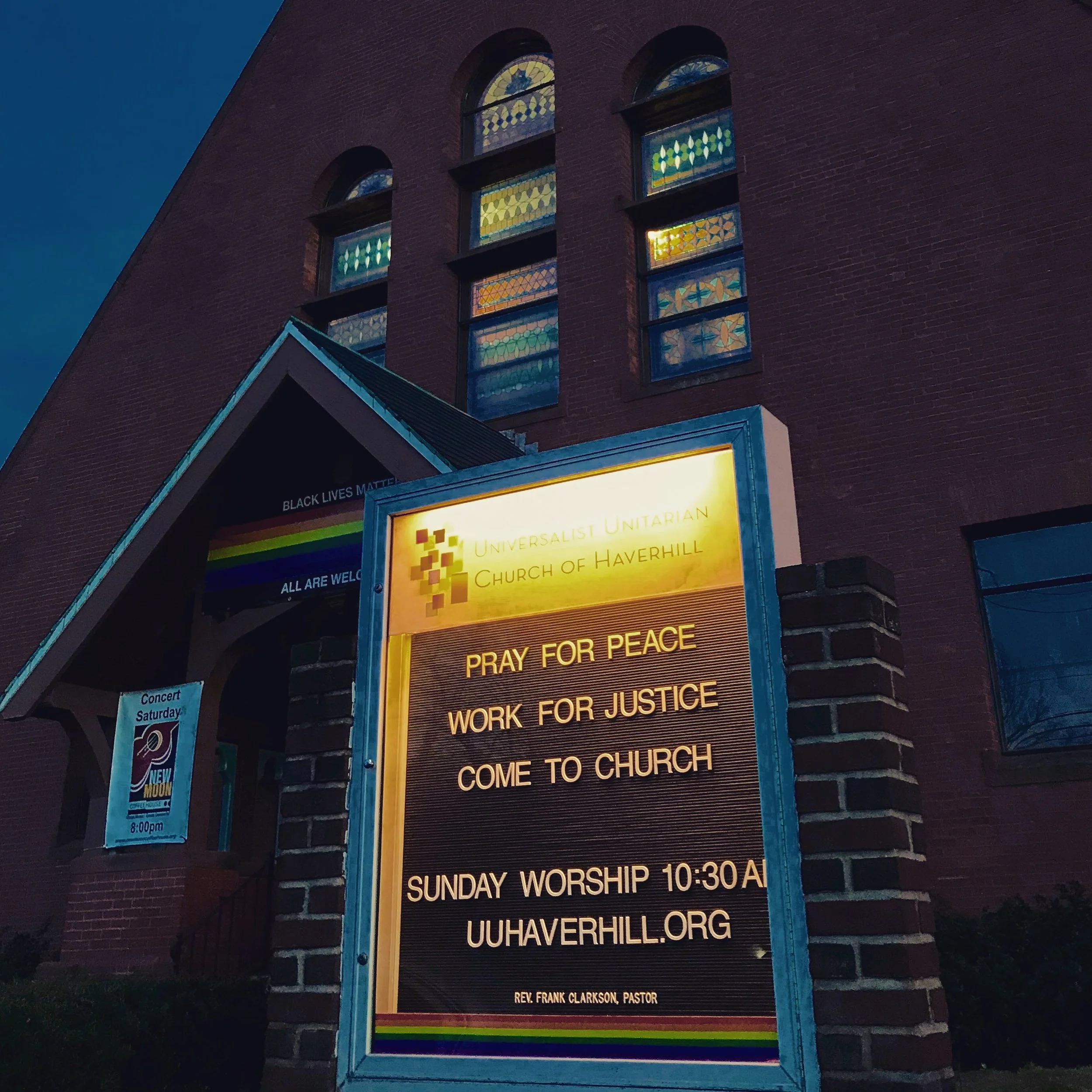

Sermon given by Rev. Frank Clarkson, October 15, 2023.

It’s been a horrific week for ordinary people in Israel and Palestine, where atrocities and suffering beyond words have happened on both sides. It’s been a heartbreaking week for anyone who cares about peace and justice, and we rightfully fear for where this violence will lead. I don’t have anything particularly wise to say about this; nor do I have the heart to say more than a few words about it. I only know that we are called to stand for peace and for justice. To resist the impulse to take sides, or to seek the false peace of neutrality, or of looking away. I take hope from people and organizations working for peace, like the Parents Circle, a group of Palestinian and Israeli families which began almost thirty years ago, when parents on both sides who had lost children to the violence said “Enough.” Enough death, enough bereaved families. These parents concluded that the process of reconciliation between nations is a prerequisite to achieving a sustainable peace. They know firsthand what the leaders need to learn, that violence only creates more violence, that the way forward has to be through justice and reconciliation.

Now, will you pivot with me back to the fall of 2000? When I attended a visiting day at Harvard Divinity School, which was a place where many UUs prepared for ministry. More than once that day I heard the expression, “rigorous academics,” which wasn’t exactly how I imagined my path toward ministry. Talking with a friend in her first year there, she said, “You could check out Episcopal Divinity School. They have these big round tables in their refectory, which I think are a symbol of the kind of community they are trying to create.”

I hadn’t considered EDS because of that word “Episcopal.” I’d left that tradition for this one. But I went to visit, and found myself drawn to this seminary which centered anti-racism and anti-oppression work, had a program in feminist liberation theology, and welcomed people from a diversity of traditions. There was at least one UU there!

My friend was right—it was a vital community that challenged me and fed my soul. We had rich conversations around those big tables, and these conversations overlapped with what was happening in the classroom and in the chapel, and I thrived there.

About a year later those old round tables were replaced with new ones; smaller, rectangular. This happens, you know—things change. Sometimes institutions and individuals disappoint us. But they were just tables. That community and those conversations continued, and I loved my three years there.

One of the first things I noticed when I came into this sturdy and beautiful building was the tables set up for coffee hour. It looked like a cafe, and this told me something about the congregation here—that you are hospitable, and you want and need ways to see and hear and connect with each other.

Do you know the expression “a third place?” It comes from a book called The Great Good Place, by the sociologist Ray Oldenburg. He says we spend most of our time at home and at work, these are places one and two, and we need a third place, which can be a cafe or coffee shop, a bookstores or a bar, a hair salon or barber shop, or a Our souls hunger for the the kind of camaraderie and conversation these places invite. Some aspects of a great good place are that it’s accessible and doesn’t care about your social class; it’s comfortable and unpretentious; you’re not required to be there, you go because you want to; it has regulars, and these regulars are ready and glad to welcome newcomers; the mood is relaxed and even playful, it’s a home away from home.

We need these these kinds of third places, for the comfort and connection they provide. And a civil society and our democracy depend on the community, the strengthening of the social fabric that happens there.

Our UU tradition, with its openness to theological diversity, and its invitation to search for truth and meaning—this makes us a good place, a third place, where people can make deep connections, do their own work, heal from wounds, find a spiritual home.

You heard this in Rev. Rosemary Bray McNatt’s story—how as a girl she was drawn to church and its promise, but how she got burned by the patriarchy, that said, “Oh no, you’ll never serve at this altar.”

“Even at 10,” she says, “I was vibrating with rage, I vowed never to belong to a church again.” But years later, she met a guy, who wanted her to go to church with him, and they got married in that church. And, she says, found the rest of her life:

“It was at once the last thing I expected and the thing I most wanted. It was in a liberal religious sanctuary that I began to heal; it was among our people that I began to hope; it was through their affirmations that I came to understand God’s call and embraced in myself what they and God saw in me—the capacity for our liberal ministry.”

Of course the story doesn’t end there. Rosemary served as a parish minister for 13 years, and now she’s the president of the UU seminary in Berkley, CA; she’s been active on the national scene, writing for and editing UU publications. Rosemary, who’s a Black woman, says that over her years in our tradition she’s changed. “What was once for me a source of wonder,” she writes, “has become, in these intervening years, more nuanced. I am not yet jaded, but I am close…. I am, however, long past being ready for genuine change.”

This is the thing about human institutions: by their nature, they are systems that are resistant to change. Do you know the joke about how many church folks does it take to change a light bulb? “Change? Change?”

But the church, to be true to its calling, has to change, has to adapt, has to grow. It can be tempting, once you find a place where you feel comfortable and at home, to want things to stay the same; to resist change, which can seem risky and threatening. But a lively and liberating third place, especially when that place is a faith community, is not meant, is not content, to be just a place for comfort and connection, as good and important as that is. A healthy sense of belonging is supposed to be a launching pad for what’s next, for the lives we are here to live, for the liberation we are her to claim and share. I hope this church lights a fire in you that stirs you up and sends you out to do the work you have been given to do.

Rosemary Bray McNatt asks,”What if Unitarian Universalism became theologically literate in more ways than those of our forefathers and foremothers? What if we came to specialize in texts of liberation? We would start with Hebrew and Christian scripture, of course, because they are our oldest heritage. But should we choose to become literate in all the texts of liberation available to us, how many doors might open? What if we chose to inform ourselves more deeply about the liberatory and celebratory message of the traditional black church? What if we made it our business to view the story of our free faith through a womanist frame, using the parameters of that theology to point our people toward more victorious living?

She goes on, “… we of liberal faith could choose to be teachable; we could choose to learn more from the black church paradigm than spirituals; we might discover a deeply rooted spirituality that could sustain us as well. And we could do the same with the many expressions of faith that have been proven in the lives of real people right now. What if we became the people of Pentecost, with tongues of liberatory fire descending upon all the people, each one of them hearing the voice of Spirit in the language they understand: this one in womanist process theology, this one in Mahayana Buddhist practice; this one in religious humanism? Her whole essay is only five pages; here’s the link.

A hundred years ago, Rev. Lewis Fisher, a Universalist minister and divinity school dean, said, “Universalists are often asked to tell where they stand. The only true answer to give to this question is that we do not stand at all, we move.”

The question before us, my companions in this lovely third place we call church, is this: for what, and for whom, are we here? Are we here only to meet our own, and each other’s needs, as important as those are? Or do we have a higher and wider calling? What does that calling look like? In which directions are we called to move? Who and what are we going to serve?

There’s so much brokenness in our world. It’s not likely that we’ll be the people to broker a new Middle East peace accord. But that doesn’t mean there isn’t good and important ministry for us to do right here, where we live, where we work, where we have influence and agency. So let us pray for peace, and work for justice. Let us who are able, do what we can, while we are here.

Who’s ready to lift your voice, and say to your companions, “Come and go with me to that land; that land of of freedom, and justice, where I’m bound, where we’re bound. And I’m not going without you.”

Amen.